Welcome !

|

|

WWW.KALOSKAISOPHOS.ORG

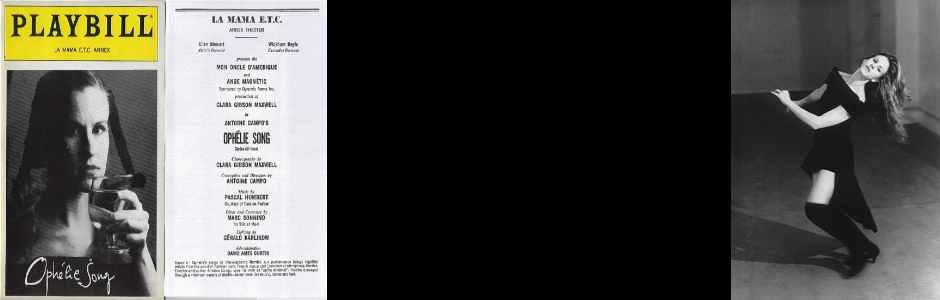

is the website of Mon Oncle D'Amérique Productions, an

"association loi 1901" based in Paris presenting the

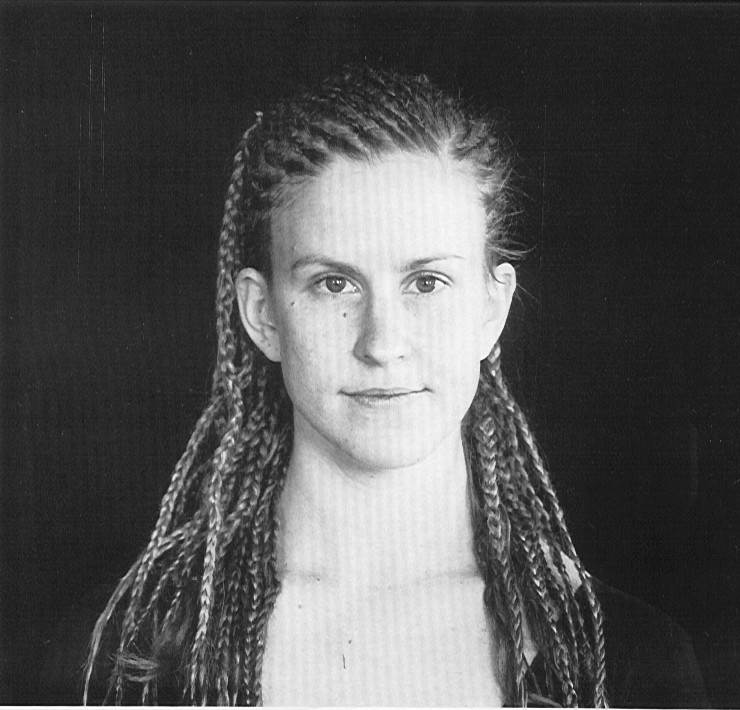

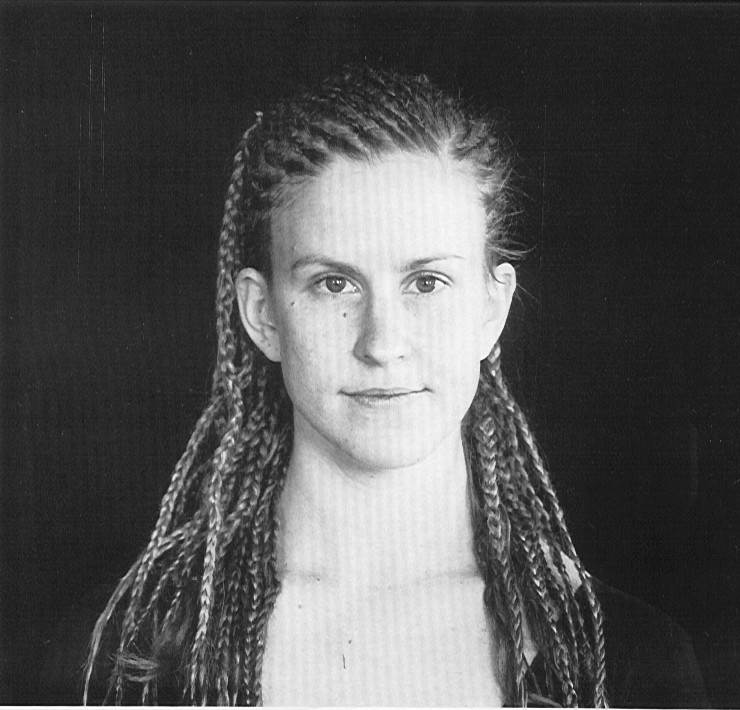

artistic collaborations of American choreographer Clara Gibson

Maxwell since 1987.

|

|

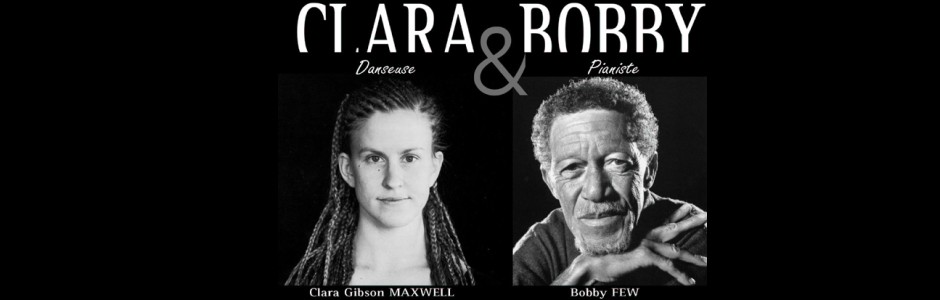

| photo

Mariana Cook |

|

photo Johannes Von Saurma

|

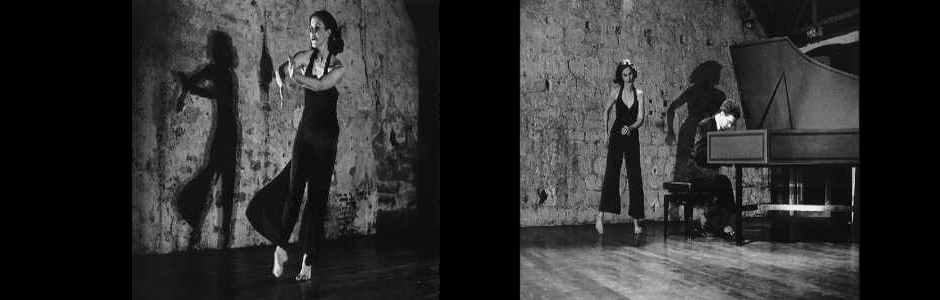

EN CLÔTURE DE L’EXPOSITION

“L’ART FAIT VENTRE”

LE MUSÉE DE LA POSTE PRÉSENTE

“SOUL KITCHEN”

ESPACE PIERRE CARDIN

3 AVENUE GABRIEL PARIS 8e

JEUDI 18 SEPTEMBRE – 19H30

TARIF : 40€ / TARIF RÉDUIT : 25 € (CODE: MODA)

SOUS SOUSCRIPTION

souscription@lesfertiles.fr

CLIQUEZ SUR L’IMAGE CI-DESSOUS

WHY

WWW.KALOSKAISOPHOS.ORG?

In

ancient Greek, "Kalos" meant "Beautiful" and

"Sophos" meant "Wise." We do not claim to be or to

incarnate "Beauty" and "Wisdom," but our creative

collective efforts are directed toward those "ends," motivated

and furthered by the love thereof. The love of Beauty and Truth is the

first condition of possibility for their imaginative re-creation, just

as the practice thereof gives one a taste of and for that love.

In the Funeral Oration from The History of the Peloponnesian

Wars (2.40), Thucydides reports Pericles declaring:

Philokaloumen te gar met ' euteleias

kai philosophoumen aneu malakias.

An initial (overly literal) shot at a translation:

For we love beauty, but with good purpose,

and we love wisdom in a way that does not make us soft.

The

English philosopher Thomas Hobbes had offered this translation c. 1628:

"For

we also give ourselves to bravery, and yet with thrift;

and to

philosophy, and yet without molification of the mind."

His

editor, David Grene, comments: "This is a magnificent

seventeenth-century sentence, but liable to misconstruction by a modern

reader. In our idiom the literal rendering is:

We are lovers of beauty, but with cheapness;

we are

lovers of culture, but without softness."

Grene

goes on to explain that Hobbes translated Thucydides' great work

"in order that the follies of the Athenian Democrats should be

revealed to his compatriots." Nevertheless, Hobbes the political

absolutist offered us this "magnificent seventeenth-century

translation" of his--one that admirably expresses the ideals of the

Athenian democracy, despite his contempt for them.

The twentieth-century philosopher Hannah Arendt also reflected--more

sympathetically, yet even more idiosyncratically than Hobbes did--on

this famous passage:

We love beauty within the limits of political judgment,

and we

philosophize without the barbarian vice of effiminacy."

In

her text "The Crisis in Culture," where this translation is

offered, Arendt's main concern was to reconcile "the

Greeks"--who, she believed, were cultureless--with Cicero and

Immanuel Kant by showing how "the Greeks" preceded these two

of her favorite thinkers in the linking of "politics" and

"art." But she also sought to highlight the differences

between "the Greeks" and, on the one hand, "the

Romans" (the latter are said to have originated culture) and, on

the other hand, "the barbarians" (the latter are said to be

viewed by the Greeks as softened by despotism)--not to appreciate the

possible connection between philosophy, democracy, and art in

ancient Athens, where this Funeral Oration was composed. Arendt thus

provides no hint that Pericles' Funeral Oration was spoken in Athens

amid a generation-long struggle of the democratic poleis

against the Spartan-led oligopolies of the time. The contrast the

Corinthians made elsewhere (1.70) between the hesitant and indecisive

Spartans, on the one hand, and the Athenians who saw no contradiction

between thought, feeling, and action, on the other, is missed entirely.

And, finally, she misconstrued the Greek "middle voice" of philokaloumen

and philosophoumen, speaking of the "love of

beautiful things" and "philosophizing" each as "an

activity" (action being one of her primary philosophical

categories), rather than as a a kind of self-transformative (and

society-transforming) process, wherein the collective passion for

democracy would be as important as any action undertaken by

individuals, great or otherwise.

The late social and political thinker, Cornelius Castoriadis, offered an

in-depth reflection upon the meaning of this phrase while criticizing

Arendt's interpretation thereof. It is worth quoting this discussion in

extenso, for here the intimate and crucial connection between

philosophy, democracy, and art is appreciated in full:

The substantive conception of democracy in Greece can be seen clearly in

the entirety of the works of the polis in general. It has been

explicitly formulated with unsurpassed depth and intensity in the most

important political monument of political thought I have ever read, the

Funeral Speech of Pericles (Thuc. 2.35-46). It will always remain

puzzling to me that Hannah Arendt, who admired this text and supplied

brilliant clues for its interpretation, did not see that it offers a substantive

conception of democracy hardly compatible with her own. In the Funeral

Speech, Pericles describes the ways of the Athenians (2.37-41) and

presents in a half-sentence (beginning of 2.40) a definition of what is,

in fact, the "object" of this life. The half-sentence in

question is the famous Philokaloumen gar met'euteleias kai

philosophoumen aneu malakias. In "The Crisis in Culture"

Hannah Arendt offers a rich and penetrating commentary of this phrase.

But I fail to find in her text what is, to my mind, the most important

point. Pericles' sentence is impossible to translate into a modern

language. The two verbs of the phrase can be rendered literally by

"we love beauty . . . and we love wisdom . . .," but the

essential would be lost (as Hannah Arendt correctly saw). The verbs do

not allow this separation of the "we" and the

"object"—beauty or wisdom—external to this "we."

The verbs are not "transitive," and they are not even simply

"active": they are at the same time "verbs of

state." Like the verb to live, they point to an

"activity" which is at the same time a way of being or rather

the way by means of which the subject of the verb is. Pericles does not

say we love beautiful things (and put them in museums), we love wisdom

(and pay professors or buy books). He says we are in and by the love of

beauty and wisdom and the activity this love brings forth, we live by

and with and through them—but far from extravagance, and far from

flabbiness. This is why he feels able to call Athens paideusis—the

education and educator—of Greece. In the Funeral Speech, Pericles

implicitly shows the futility of the false dilemmas that plague modern

political philosophy and the modern mentality in general: the

"individual" versus "society," or "civil

society" versus "the State." The object of the

institution of the polis is for him the creation of a human

being, the Athenian citizen, who exists and lives in and through the

unity of these three: the love and "practice" of beauty, the

love and "practice" of wisdom, the care and responsibility for

the common good, the collectivity, the polis ("they died

bravely in battle rightly pretending not to be deprived of such a polis,

and it is understandable that everyone among those living is willing to

suffer for her" 2.41). Among the three, there can be no separation;

beauty and wisdom such as the Athenians loved them and lived them could

exist only in Athens. The Athenian citizen is not a "private

philosopher," or a "private artist," he is a citizen for

whom philosophy and art have become ways of life. This, I think, is the

real, materialized, answer of ancient democracy to the question about

the "object" of the political institution. When I say that the

Greeks are for us a germ, I mean, first, that they never stopped

thinking about this question: What is it that the institution of society

ought to achieve? And second, I mean that in the paradigmatic case,

Athens, they gave this answer: the creation of human beings living with

beauty, living with wisdom, and loving the common good.

REFERENCES:

Thucydides.

The Peloponnesian War. 2 vols. Trans. Thomas Hobbes. Ed. David

Grene. With an introduction by Bertrand de Jouvenel. Ann Arbor: The

University of Michigan Press, 1959.

Hannah

Arendt. "The Crisis in Culture." Between Past and Future:

Six Exercises in Political Thought. New York: The Viking Press,

1961.

Cornelius

Castoriadis. "The Greek Polis and the Creation of

Democracy" (1983). Philosophy, Politics, Autonomy. Ed. David

Ames Curtis. New York: Oxford University Press, 1991.